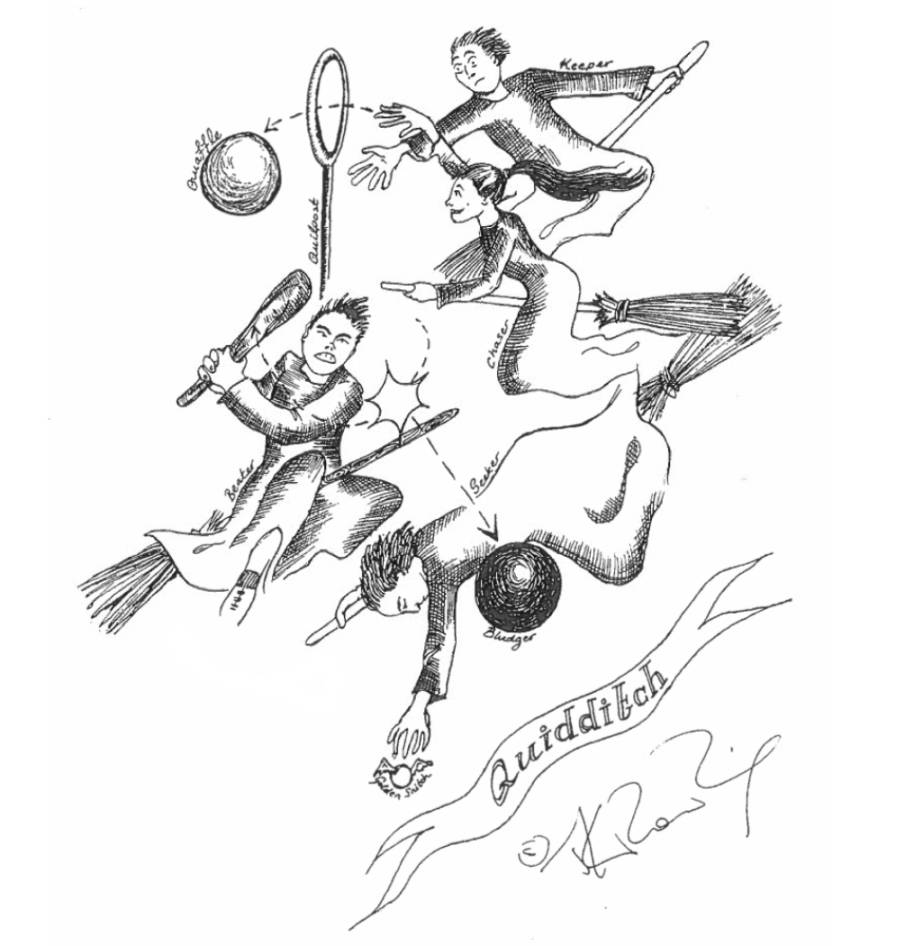

As only European teams competed during the fifteenth and sixteenth centuries, purists prefer to date the Quidditch World Cup’s inception from the seventeenth century when it became open to all continents. There is also heated debate about the accuracy of some historical accounts of tournaments. A substantial amount of all post-game analysis centres on whether magical interference took place and whether it made, or ought to have made, the final result moot.

The ICWQC has the unlucky job of regulating this contentious and anarchic competition. The rulebook concerning both on- and off-pitch magic is alleged to stretch to nineteen volumes and to include such rules as ‘no dragon is to be introduced into the stadium for any purpose including, but not limited to, team mascot, coach or cup warmer’ and ‘modification of any part of the referee’s body, whether or not he or she has requested such modification, will lead to a lifetime ban from the tournament and possibly imprisonment.’

A source of vehement disagreements, a security risk for all who attend it and a frequent focus for unrest and protest, the Quidditch World Cup is simultaneously the most exhilarating sporting event on Earth and a logistical nightmare for the host nation.

Statute of Secrecy

A watershed moment for the Quidditch World Cup was the implementation of the International Statute of Secrecy in 1692, which was intended to conceal the existence of magic and wizards. The International Confederation of Wizards (ICW) saw the Quidditch World Cup as a security risk of the highest magnitude because of the mass movement and congregation of so many members of the international wizarding community. However, following mass protests and threats to the ICW, it was agreed that the tournament could continue and a regulatory body – the ICWQC – was set up to locate suitable venues – usually remote moors, deserts and deserted islands – arrange transportation for spectators (as many as a hundred thousand routinely attend finals) and police the games themselves, a task generally agreed to be among the most thankless and difficult in the wizarding world.

How the Tournament Works

The number of countries that enter a Quidditch team for each World Cup fluctuates from tournament to tournament. Where the wizarding population of a country is small it can be difficult to raise a team of the required standard, but other factors such as international conflict or disaster may affect the entry numbers. However, any country may enter a team within the twelve months following the last final.

Teams are then divided into sixteen groups within which every team plays all the others over a two-year period until sixteen winning teams remain. During the group phase, game length is capped at four hours to prevent player exhaustion. Inevitably this means that some group games have no Snitch catches, but are decided on goals alone. Any win in the group phase counts for two points. A win by more than 150 points earns an additional five points, by 100 an additional 3 points and 50, 1 point. In the case of a tie on points, the winner is the team who caught the Snitch most often – or most quickly – during its matches.

The final sixteen are ranked according to the points they won during the group phase. The team with most points plays the team with least, the team with the second most points plays the team with the second least and so on. In theory, the two best teams will remain to play each other in the final.

Referees are chosen by the ICWQC.

Infamous Tournaments

No Quidditch World Cup is without its controversies, but some stand out. A few of the most infamous are listed below.

Attack of the Killer Forest

The ghastly climax of the 1809 final between Romania and New Spain (what is now known as Mexico) has gone down in wizarding history as the worst exhibition of temper ever given by an individual player. Niko Nenad’s teammates had become so concerned by his ferocious outbursts during the quarter and semi-finals that they tried to persuade their manager to substitute him for the final, advice that was sadly ignored by the ambitious old wizard. After the game, Nenad’s teammate Ivan Popa (winner of an International Wizarding Order of Merit for his life-saving actions during the catastrophe) told an international inquiry: ‘Over the preceding weeks we’d seen Niko beat himself over the head with his broom and set fire to his own feet in frustration. I’d personally stopped him strangling two referees. However, I had no suspicion about what he was planning to do if the final didn’t go our way. I mean, who’d suspect that? You’d have to be as mental as he was.’ Precisely when and how Nenad managed to jinx an entire forest on the edge of the West Siberian Plain is open to speculation, although he is thought to have had accomplices among unprincipled fans and was later proven to have paid local Dark wizards substantial sums. After two hours of play, Romania were behind on points and looking tired. It was then that Nenad deliberately hit a Bludger out of the stadium into the forest beyond the pitch. The effect was instantaneous and murderous. The trees sprang to life, wrenched their roots out of the ground and marched upon the stadium, flattening everything in their path, causing numerous injuries and several fatalities. What had been a Quidditch match turned swiftly into a human versus tree battle, which the wizards won only after seven hours’ hard fighting. Nenad was not prosecuted as he had been killed early on by a particularly violent spruce.

The Tournament that Nobody Remembers

The ICWQC insists that a tournament has been held every four years since 1473. This is a source of pride, proving as it does that nothing – wars, adverse weather conditions or Muggle interference – can stop wizards playing Quidditch. There is, however, a mystery surrounding the tournament of 1877. The competition was undoubtedly planned: a venue chosen (the Ryn Desert in Kazakhstan), publicity materials produced, tickets sold. In August, however, the wizarding world woke up to the fact that they had no memory whatsoever of the tournament taking place. Neither those in possession of tickets nor any of the players could remember a single game. However, for reasons none of them understood, English Beater Lucas Bargeworthy was missing most of his teeth, Canadian Seeker Angelus Peel’s knees were on backwards and half the Argentinian team were found tied up in the basement of a pub in Cardiff. Precisely what had – or had not – taken place during the tournament has never been satisfactorily proven. Theories range from a Mass Memory Charm perpetuated by the Goblin Liberation Front (at that time very active and attracting a number of disaffected anarchist wizards) or the breakout of Cerebrumous Spattergroit, a virulent sub-strain of the more common Spattergroit, which causes severe confusion and memory impairment. In any case, it was deemed appropriate to re-stage the tournament in 1878 and it has been held every four years since, which accounts for the slight anomaly in the ‘every four years since 1473’ sequence.

Royston Idlewind and the Dissimulators

In 1971 the ICWQC appointed a new International Director, Australian wizard Royston Idlewind. An ex-player who had been part of his country’s World Cup-winning team of 1966, he was nevertheless a contentious choice for International Director due to his hard-line views on crowd control – a stance undoubtedly influenced by the many jinxes he had endured as Australia’s star Chaser. Idlewind’s statement that he considered the crowd ‘the only thing I don’t like about Quidditch’ did not endear him to fans. Their feelings turned to outright hostility when he proceeded to bring in a number of draconian regulations, the worst being a total ban on all wands from the stadium except those carried by ICWQC officials. Many fans threatened to boycott the 1974 World Cup in protest but as empty stands were Idlewind’s secret ambition, their strategy never stood a chance. The tournament duly commenced and while crowd turnout was reduced, the appearance of ‘Dissimulators’, an innovative new style of musical instrument, enlivened every match. These multi-coloured tube-like objects emitted loud cries of support and puffs of smoke in national colours. As the tournament progressed, the Dissimulator craze grew, as did the crowds. By the time the Syria-Madagascar final arrived, the stands were packed with a record crowd of wizards, each carrying his or her own Dissimulator. Upon the appearance of Royston Idlewind in the box for dignitaries and high-ranking officials, a hundred thousand Dissimulators emitted loud raspberries and were transformed instantly into the wands they had been disguising all along. Humiliated by the mass flouting of his pet law, Royston Idlewind resigned instantly. Even the supporters of the losers, Madagascar, had something to celebrate during the rest of the long, raucous night.

Reappearance of the Dark Mark

Possibly the most infamous World Cup Final of the last few centuries was the Ireland-Bulgaria match of 1994, which took place on Dartmoor, England. During the post-match celebrations of Ireland’s triumph there was an outbreak of unprecedented violence as supporters of Lord Voldemort attacked fellow wizards and captured and tortured local Muggles. For the first time in fourteen years, the Dark Mark appeared in the sky, which caused widespread alarm and resulted in many injuries among the crowd. The ICWQC censured the Ministry of Magic heavily after the event, judging that security arrangements had been inadequate given the known existence of a violent pure-blood tendency in the United Kingdom. Royston Idlewind emerged briefly from retirement to give the following statement to the Daily Prophet: ‘A wand ban doesn’t look so stupid now, does it?’

Quidditch World Cup (1990-2014)

1990

Canada 270 – Scotland 240

A bitter disappointment for Scotland, whose Seeker Hector Lamont missed catching the Snitch by millimetres. In a post-match interview, Hector famously lambasted his father (‘Stubby’ Lamont) for not giving him longer fingers.

1994

Ireland 170 – Bulgaria 160

The on-pitch action was very much overshadowed by the events that followed this match. A spectacular Snitch capture by young Seeker Viktor Krum was enough to salvage Bulgarian dignity, but not to secure a win.

1998

Malawi 260 – Senegal 180

Only the second ever all-African final. Following the 1994 riots, security at this match was tighter than ever before. Senegal almost refused to play when their team mascots (Yumboes) were arrested outside the stadium. Yumboes are a kind of African house-elf and they took their arrest in reasonably good part, merely stealing every bit of food within a ten-mile radius in revenge and vanishing into the night.

2002

Egypt 450 – Bulgaria 300

Another crushing disappointment for Bulgaria. Viktor Krum was narrowly beaten to the Snitch by the outstanding Egyptian Seeker, Rawya Zaghloul. After the match, a tearful Krum announced his retirement.

2006

Burkina Faso 300 – France 220

A popular win for the small African nation, whose Seeker Joshua Sankara was promptly named Burkinabé Minister for Magic. Two days later he resigned, pointing out that he’d much rather play Quidditch.

2010

Moldova 750 – China 640

A furiously contested match that lasted three days and was widely held to have produced some of the finest Quidditch seen this century. The tiny country of Moldova has consistently produced excellent Quidditch teams and supporters were heartbroken that they failed to qualify this year due to an outbreak of Dragon Pox at their training camp.

The Quidditch World Cup 2014

This year’s Quidditch World Cup promises to be as exciting as ever. The sixteen competing countries are:

Brazil, Bulgaria, Chad, Fiji, Germany, Haiti, Ivory Coast, Jamaica, Japan, Liechtenstein, New Zealand, Nigeria, Norway, Poland, USA and Wales.

Nigeria and Norway enter the tournament as the two highest ranked teams. This is the first year that the USA is thought to have a reasonable chance of reaching the final. Much interest has been generated by the return to the Bulgarian side of the previously retired Viktor Krum, who at 38 is old for a Seeker but whose stated aim is ‘to win the World Cup before I die.’ For this reason, Bulgaria is attracting support from those whose own countries have not qualified.

Liechtenstein caused a serious upset in the qualifying stages by winning the group over last year’s runners-up, China. Liechtenstein’s team mascot is a gloomy, oversized Augurey called Hans who has his own fan club.

Other than this, nothing out of the ordinary has been reported. Rumours that Haiti have used Inferi to intimidate opposing teams have been dismissed by the ICWQC as ‘malicious and baseless.’ Accusations that Polish Seeker Bonawentura Wójcik is actually the famous Italian Seeker Luciano Volpi, Transfigured, were only disproven when Luciano Volpi agreed to a press conference by Wójcik’s side. Welsh manager Gwenog Jones, formerly of the Holyhead Harpies, threatened to ‘curse the face off’ rival Brazilian manager José Barboza when he called her Chasers ‘talentless hags’, a comment he later insisted had been taken out of context.

Opening games will take place next month in the Patagonian desert.